Broad Sides

featured interview & images

“every house is haunted when you bring your own ghosts”

Interview with Broad Sides (Dana Koster & Chelsea America)

HMR: Can you talk about how you met, and about how your collaboration got started? What is it about collaborative art making that interests you? How does this collaboration relate to your individual practices as an artist or writer?

CA: Dana was going to display poems at the local coffee shop and approached me about doing a visual component. I created two large paintings inspired by her work to show alongside her poetry. Somewhere during the planning process, I believe Dana suggested she write some things in response to my work because I had created the paintings based on her poems. We selected an area of the cafe, and the plan was that I would put up lots of small sketches and she would come in and write on them and we would keep adding to the wall for the duration of the show, allowing things to accumulate.

DK: My oldest kid and Chelsea’s youngest kid are the same age, and we enrolled them at a wonderful (and, at times, maddeningly) parent participation preschool at the same time. That month, I saw an art show at my favorite coffee shop in town, and the paintings were so weird and witty and frightening – the piece that sticks out in my mind is a big watercolor of a topless woman in a wolf mask, perched on all fours, breastfeeding an infant. Then I saw a flier for that art show on the front of our little preschool and realized the artist was a fellow mom in my son’s class. I had to meet her! It probably goes without saying, but a lot of women stop creating art when they have small children, so this was a really important connection. As to how our collaboration relates to my individual practice – I guess I would say that it runs parallel to my poetics. Writing Broad Sides is helpful to my poetry in the sense that it’s a quick creative exercise that I can do when I don’t have time to sit down and compose a poem (so, most of the time). It exercises my comedy more than my poetry – my poems tend to be a lot darker than what I write for this project.

HMR: How would you describe the aesthetic of your work? Who do you consider to be your most prominent influences? How do you see your work situated in the landscape of contemporary text-image artwork, or with regard to other art forms or disciplines?

CA: The aesthetic has a pulpy, narrative feel, with a nod to classic illustration, and is rendered with loose, layered, uncontrolled watercolor in technicolor hues. There are so many great artists who have used image and text. As far as personal influence, Raymond Pettibon is someone I look to a lot, with his imagery ranging from the personal to the political. Other inspiration comes from the washed out glimpses of suburbia offered by David Hockney and Wayne Thibauld, and the way Francesca Woodman uses the body as a narrative tool. I am also very fond of the high drama in film stills from other eras, particularly film noir.

DK: I could tell from the first time I saw Chelsea’s work that she covered a lot of the same themes I do in my poetry. I’ve referred to our mutual aesthetic before as “dark domesticity” – we love our kids but we don’t sugarcoat parenthood. The ferocity of motherhood, the way that it hijacks one’s body/mind/life, these ideas were already central to what both of us were doing, separate from one another. That said, our biggest influence is actually a childless man! We both grew up loving Ashleigh Brilliant’s “Pot Shots,” which ran in newspapers when we were growing up. He mixes illustration with short, witty sentences, so it’s not too hard to draw an ancestral line from his work to ours. You can still find his work in the form of postcards in small bookstores.

HRM: Often the images and texts in your pieces work to unsettle social norms, especially concerning gender, sex, violence, and affect. Can you talk about what it’s like to produce this kind of art right now, in a cultural moment like ours?

CA: Our work is definitely all of that, with a strong dose of satire. I think the humor can provide accessibility into the darker or more difficult content.

DK: I honestly don’t even think about it. I wouldn’t have thought of our work as political, though obviously, once you pointed it out, it absolutely is. Most of what we’ve created is some sort of subversion. There are women stabbing men, smoking, wrestling, eating, screaming, grimacing. I’ve also written tons of Broad Sides about explicitly political issues like sexism, capitalism, colonialism, gun violence. I would guess that I didn’t register it because just living in a woman’s body is political right now, especially one that’s fat (like mine). I’m also super aware of all the ways that my body is privileged by being white, by being cis-gendered. I’m privileged to have financial security, education, a loving partner, the exact number of children that I wanted. These are all things I think about as I move through my life. I can’t imagine not using them in my art.

HMR: Can you describe your collaborative process? Do you have “rules of engagement” or other strategies for sharing your work with each other equitably, respectfully? How do you make decisions about how to develop a piece from start to finish?

DK: We have zero rules of engagement, and we actually work completely independently of one another. We honestly don’t talk about the pieces at all. Every few weeks, Chelsea will stash a big stack of art in my mailbox and then I just… write words on the page. 99% of the time, I post the finished Broad Side to Instagram before she even sees it. I think the way the pieces work as cohesive wholes has more to do with how well our personalities and aesthetics match than any active planning on our parts.

CA: What Dana said.

HMR: To what extent do you weigh the audience’s response as a factor in your process, or in developing your aesthetic? How does your social media presence shape your sense of audience, if at all?

CA: I never think of the audience at all during the process of making work. I think the audience comes into play when the work hits the world. The audience completes the work when they find value in what we make or find our work makes tangible their feelings.

DK: Oh my God, I feel like I keep answering “I don’t think about that at all” when I go to answer these questions. I swear that I do put thought into this project! I’m just old enough to understand that as an artist, I can’t think about the audience’s response at all, or I’ll never create anything. I have way too much anxiety to consider what people will think about something I make. I will say, though, that our social media followers are hilarious and gutsy and weird, and even if we don’t make our art for them, it does make me happy to think there are so many Difficult Women (and men) out there and that our account has self-selected them. The world needs more people who are willing to call it on its bullshit!

HMR: Which of your pieces best exemplify your aesthetic / your collaboration / your goals as artists? Can you describe a specific work that’s especially memorable for you? Why?

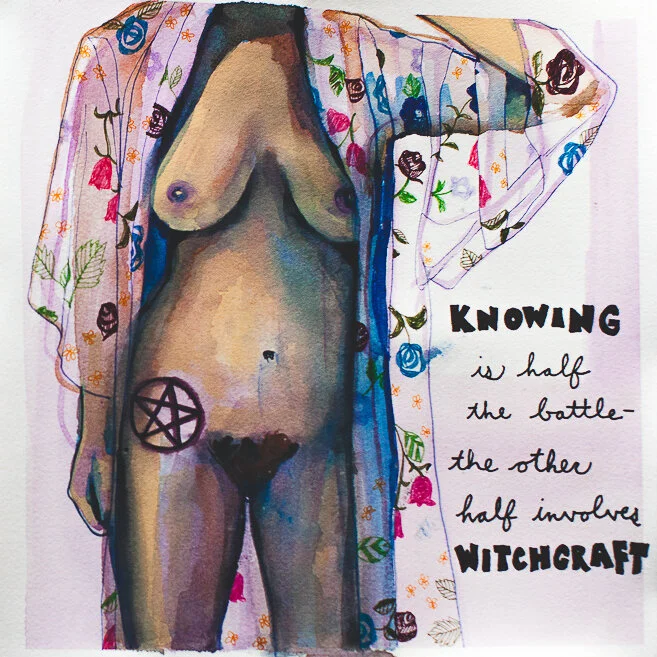

DK: When Chelsea sends something particularly stunning or strange my way, I feel really pressured to write something amazing to match. Her talent eggs me on. It actually took me a long time to feel like my words were improving, rather than ruining, her art. My favorite pieces tend to be the ones that were already the most intricate or colorful or evocative before they made it to my kitchen table. We’ve made literally hundreds of pieces at this point, but I think my favorite it still one of the first ones we made. It’s a gorgeous painting of a nude woman with a pentagram tattooed on her hip that says “knowing is half the battle – the other half involves witchcraft.” Neither of us are witches, but I think we both love the threat and the power that they imply, which is why they’re a recurring theme in our work. Maybe we wish we were witches. It’s like Morticia Addams said of her great aunt Calpurnia: “She was burned as a witch in 1706. They said she danced naked in the town square and enslaved the minister… But don’t worry. We’ve told Wednesday: college first.”

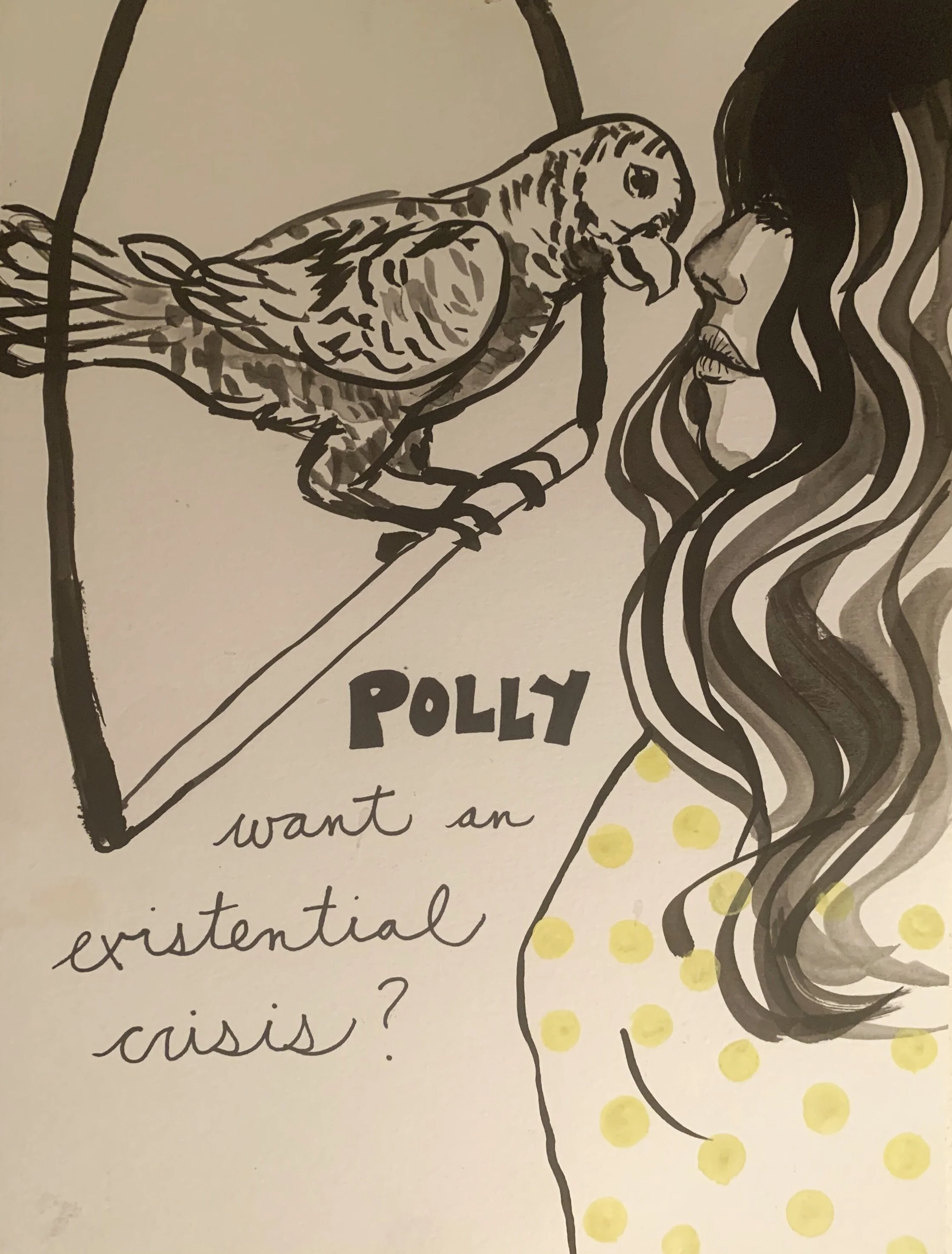

CA: My personal favorite is an ink painting I did of a woman looking at a parrot. Dana’s text reads: “Polly want an existential crisis?”

HMR: What goals, near- or long-term, do you have for Broad Sides? Do you anticipate any future collaborative projects with each other, or with others?

DK: We’d love to show at more galleries and to create some larger pieces together. We’ve also kicked around the idea of a zine, but someday I would love to create an honest-to-God coffee table book with saturated color and nice, heavy paper. Okay, now I’m drooling.

“knowing is half the battle - the other half involves witchcraft”

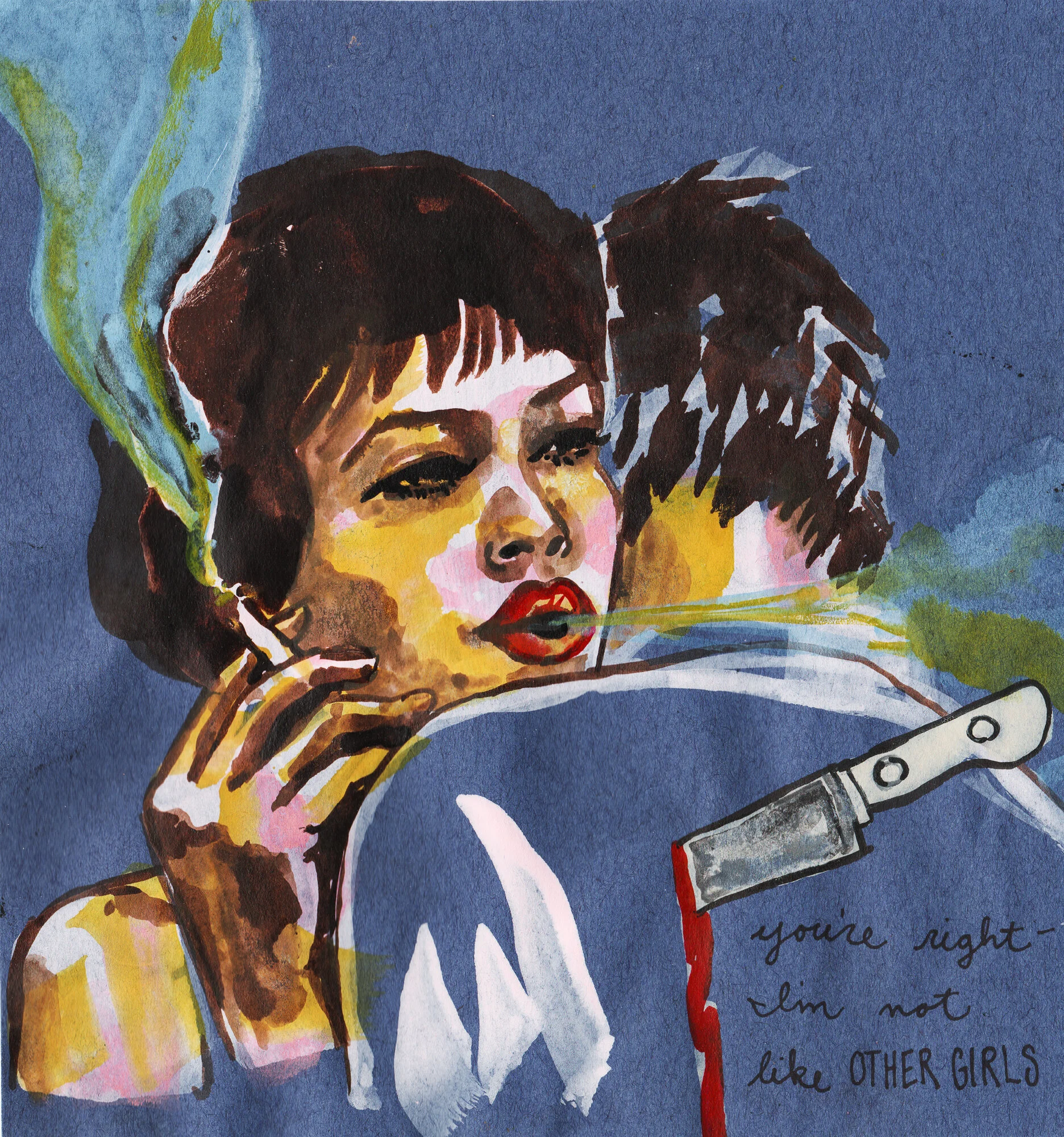

“you’re right - I’m not like other girls”

“Polly want an existential crisis?”

Broad Sides is a collaboration between poet Dana Koster and artist Chelsea America. Follow them on Instagram at @broad.sides.